The older I get the more I miss my father.

He died in the winter of 1969 at Homestead Hospital, which was referred to in those days as “the Mesta Hospital.”

He was retired after working for 35 or so years at Mesta Machine Company in West Homestead. He was a machinist, a drill press operator. His two younger brothers, Rich and Robbie, also worked for over 30 years at Mesta. My brother Dan went to Pitt on a Mesta scholarship and moved up the ranks to become the treasurer.

I never walked across the bridge to enter the building. I didn’t want to work there. Now I wish I had crossed the bridge to see where all the O’Briens worked.

My dad holds me in his arms in 1942.

When I have done book signings at area malls, when the malls had book stores in them, former co-workers of my father would share stories about him. They all seemed to like him, respect him and they told me he shared his tools with them and showed them how to do things. They referred to themselves as “greenhorns” who had a lot to learn. No one uses that word any more.

It made me feel good to hear those stories, most often at Century III Mall in West Mifflin. I like to teach and it made me feel proud to know my dad, in his own way, was a teacher, too

A boyhood friend of mine, Jack Munsie, a former Allegheny County police officer who lives in Munhall, recently told me some stories about my dad.

“When I came to see you,” said Munsie, “you might be somewhere else in the house. Your dad would invite me into the kitchen, and he’d talk to me. Not too many dads did that. He’d ask me if I wanted something to eat. He said he’d make a hamburger for me, stuff like that.

“I always liked your dad. He made me feel welcome. He’d say, ‘Jim will be down in a minute. So what’s new with you, Jack.’ He made me feel important. Yeah, your dad was a good guy.”

My day always took pride in showing up for work on time on Monday, even if he’d gotten wasted at the local bars over the weekend. If Art Rooney Jr. can be honest with me and say – “Hey, let’s face it, my dad was a racketeer.” – I think I can do the same and say my dad drank too much and smoked too much, and it led to his early demise with emphysema.

I remember Dr. Dee, the Mesta doctor, coming through the parking lot at Homestead Hospital and telling me my dad had just died. I could have been there sooner, but I never got dressed so slowly in my life as I did that morning when I got the call. I still see the ghost of Dr. Dee whenever I visit West Field in Munhall.

Art Rooney Jr. tells me his father was demanding of his five boys, making sure they did this and did that. He could be rough on them. I could never say that about my father. He was never in my face. He liked me; I always knew that.

“He was proud of all you kids,” my mother would often tell me.

He didn’t know how to drive, which is why we didn’t have a car. “But he took you kids everywhere,” my mother would add. We would take the streetcar or streetcars to places such as the Highland Park Zoo or Kennywood Park.

Sometimes we would take the train to Bridgeport, Ohio, my mother’s hometown, and the only place I ever traveled to out of state before I went to Pitt in 1960 and soon got to accompany the school’s sports teams to New York and Notre Dame and Miami and Seattle.

Mary and Dan O’Brien in the backyard of 5410 Sunnyside Street in Glenwood in the mid-50s.

I drove through Hazelwood and Glenwood on Father’s Day, a few years ago – and I could still see my dad, and my mother, on the main street, Second Avenue, and in our old neighborhood on Sunnyside Street. So many landmarks are missing – such as the Hazelwood Bank, the Hazelwood Hardware and the State Store, where my mother was a clerk for many years. Isaly’s and the Lawrence Drug Store, where we often ate lunch, are all gone, along with Duffy’s Restaurant and the Virginia Lounge.

To be honest, just about everything is missing. I wonder how long they can keep the candles burning at St. Stephen’s Church, where Kathie and I wed 50 years ago this past August 12th.

Our home is gone. It was leveled about five years ago. Most of my neighbors’ homes are gone and the empty space that is there does not look big enough to have accommodated all those homes. The old gray wooden mansion that sat across the street from our home is gone, and so are “The Flats,” a three-story string of what they called “railroad car” apartments. Where did they all fit? How did so many kids fit in some of those apartments in “The Flats”?

The B&O Railroad Yard is missing where my Grandfather Burns worked and where my Dad went to work when he was 15. My dad dropped out of school and lied about his age to get a job. After a few years at the B&O, he moved on to Mesta Machine Company. He took the streetcar each night and crossed over the Glenwood Bridge. Mesta was about three or four miles from our home.

He worked what they called “the graveyard shift” from 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. My father-in-law, Harvey Churchman Jr., worked the same shift at Westinghouse Electric Co. in East Pittsburgh. That’s gone, too.

Everyone who lived in my boyhood home is gone now. When we travel to and from Columbus to visit our daughter Sarah, her husband Mathew Eapen, and our four grandchildren, I often stop at the Mount Calvary Cemetery on National Road in Wheeling, West Va. To say hello and goodbye to my family.

The plot in the front corner of the cemetery belonged to my mother’s family. Her mother and dad were buried there first. Then came my dad. My brother Dan is buried there. My sister Carole and her family are buried there. My oldest brother Richard is buried with his family elsewhere in the cemetery. I say hello to him, too. I turned down my mother’s invitation to be buried in her family’s plot. “I’m a Pitt man,” I told her, “and there’s no way I am going to be buried in West Virginia.”

Because the plot belonged to my mother’s family, my father’s tombstone identifies him as SON-IN-LAW. The final indignity.

When I discuss my wishes for whenever I die with my wife Kathie, she often kids me by saying, “I’m going to have SON-IN-LAW etched on your tombstone.”

Kathie recalls being in the company of my father only a few times in the first three years of our relationship. She said he was always nice to her, a pleasant man.

I was away in the Army for two of the 28 years my father was alive in my life, so I never got to know him well as an adult. There are lots of questions I would like to ask him.

I felt responsible to look after him from the time I was 10 or 11 years old. I wanted to make sure he was okay. Us kids didn’t require the applause or approval of our parents to play games. We decided each day what we’d be doing sports-wise or game-wise that day. We knew to be home when the street lights came on.

My dad a handful of sports medals tucked away in a chest of drawers in his room. I took them out a few times. He had won them in track and field and in swimming in City Recreation-sponsored events. I started my own track and field team on Sunnyside Street for kids who were younger than me when I was 14.

I walked off a quarter-mile oval where you ran up the sidewalk and took a turn into the street to finish the race. When my father was 50, I urged him to run the quarter-mile. He did and when he finished the race I started feeling guilty that I might have killed the old man. After all, he was 50. I will turn 75 this summer and I have to smile now about thinking my dad was so old.

I don’t think we ever played catch with a baseball or softball.

I think I have always been independent and resourceful. I made most of my decisions myself. I thought a lot about my dad on Father’s Day. I have often said I didn’t mourn the death of my mother because she was 96 and I’d had a great mother for longer than most, and I didn’t get cheated in any respect.

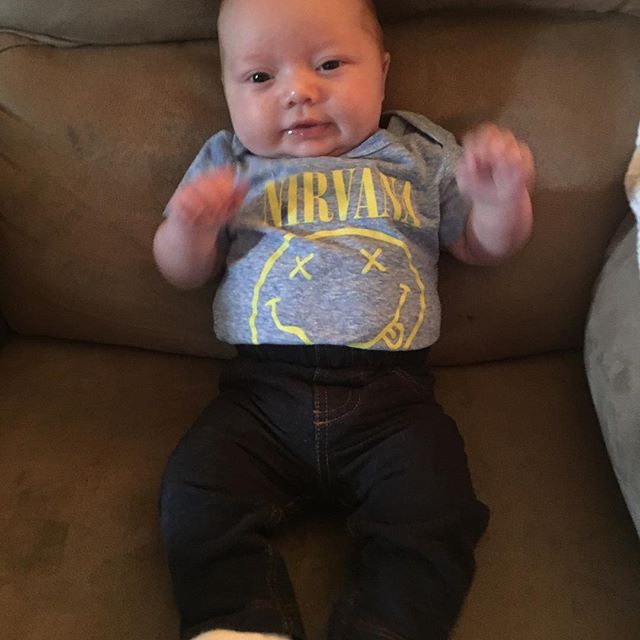

With my dad, I felt like I got cheated. I didn’t have him long enough to really get to know him. I think about my parents and Kathie’s parents and wish they could come to our new home and get to meet our children and grandchildren. They’d love them so much and they’d be so proud.

I found a dime and two shiny pennies in a parking lot on a recent Monday. I often find coins in the streets. My father used to boast about all the coins he found while walking. I’d like to think he’s throwing me pennies from heaven just to make sure I am looking where I am walking.

My brother Danny, sister Carol, Dad and our dog Pal in backyard of 5413 Sunnyside Street. That’s yours truly in the front.

Jim O’Brien is the author of 29 books in his Pittsburgh Proud sports series, including “The Chief” and “Lambert.”

My brother Danny, sister Carol, Dad and our dog Pal in backyard of 5413 Sunnyside Street. That’s yours truly in the front.