“Dare to Believe” is back this month in place of our usual streaming column. Streaming will be back in February if there is anything exciting to watch.

In honor of Martin Luther King Jr’s birthday, I’m featuring two civil rights advocates, Ella Baker and Roy Wilkins, who dedicated their lives to promoting desegregation and ending racial discrimination using Dr. King’s nonviolent methods.

Ella Baker (1903-1986) was born in Norfolk, Virginia. Her father worked on a steamship line and was often away, so her mother took on boarders to earn extra money. After a race riot in which whites attacked black workers from the shipyard, Mrs. Baker took her children to her hometown in North Carolina while Mr. Baker kept working at the shipyards.

Her maternal grandmother often told stories about being raised in slavery and the indignities she witnessed and suffered. Baker learned early in life to recognize the similarities between the treatment of enslaved people and the oppression of African Americans under Jim Crow laws.

Baker attended Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina graduating with valedictorian honors.

From 1930 – 1937, she worked as the editorial assistant at the Negro National News. Baker joined the Young Negroes Cooperative League to help develop black economic power through the establishment of collective networks. She eventually became its national director.

Baker believed in grassroots organizing and radical democracy and was often critical of professional charismatic leaders who relied on popularity over substance.

She taught courses in consumer education, labor history, and African History as part of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal Worker’s Education Project to help empower people to take control of their own destinies by fighting for social change.

In 1938, Baker became a member of the NAACP (the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). In 1943, she became their highest-ranking woman leader. She understood that equality must also include gender equality. Baker wanted to foster a system of egalitarian rights within the NAACP instead of a centralized leadership structure composed mainly of men.

She began traveling through the South meeting and getting to know hundreds of black families to encourage them to join the NAACP. While organizers from the North tended to talk down to rural southerners, Baker respected and embraced them as equals.

After the success of the Montgomery bus boycott, Baker joined the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). She worked behind the scenes organizing events and teaching the importance of nonviolent protesting methods.

Following the success of regional desegregation sit-ins by black students and their allies, Baker convinced the SCLC leadership to invite southern university students to a leadership conference. At the conference, she stressed the need for young members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to remain independent of “leader-centered orientation” which tended to be more conservative and slower to act.

Baker resented the misogyny she saw at the SCLC and decided to concentrate her efforts to help the SNCC. Under her guidance the SNCC focused its efforts on two directions, direct action, and voter registration. Baker helped members of the SNCC to coordinate efforts with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) for the region-wide Freedom Rides of 1961.

Baker maintained that “strong people do not need strong leaders,” espousing the belief that only strong participation in democracy can force leaders to recognize and respect the will of the people instead of allowing them to act in their own self-interests.

She influenced future civil rights leaders such as Julian Bond, Bob Moses, Bernice Johnson Reagon, Stokely Carmichael, Diane Nash, and Curtis Muhammad.

In 1964, Baker helped organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party as an alternative to the all-white Mississippi Democratic Party. Though they were met with heavy resistance, the party managed to elect many black leaders in Mississippi and force a rule change to allow women and minorities to sit as delegates at the Democratic National Convention.

From 1962-1967, Baker was a staff member of the Southern Conference Education Fund, an organization dedicated to helping blacks and whites work together for social justice.

She remained an activist until her death in 1986.

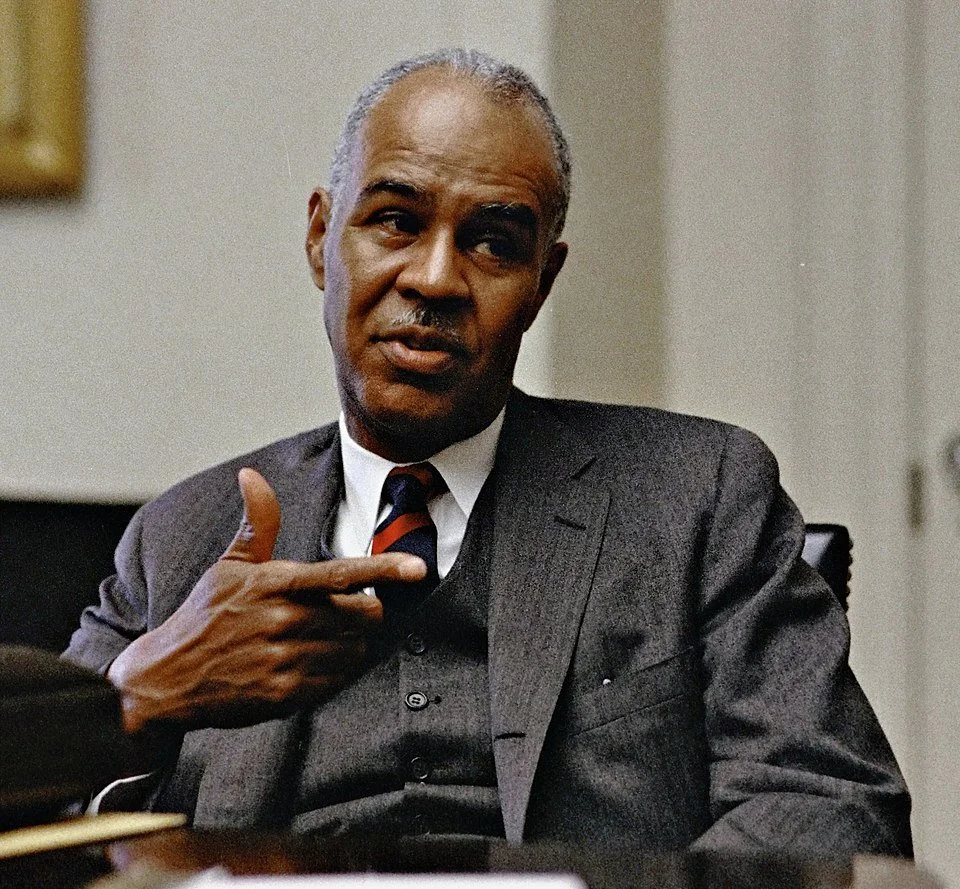

Roy Wilkins (1901-1981) was an American civil rights leader from the 1930 to the 1970s. He was born in St. Louis, Missouri. Shortly before his birth, Wilkin’s father was forced to flee St. Louis to avoid being lynched for refusing to yield the sidewalk to a white man.

Wilkins’ mother died of tuberculosis when he was four. He and his siblings went to live with an aunt and uncle in St. Paul, Minnesota where they attended local schools.

Wilkins graduated from The University of Minnesota with a degree in sociology. His wife was also a social worker.

While still in college, Wilkins was a journalist at The Minnesota Daily and become editor of The Appeal, an African American newspaper. He later became the editor of The Call, an African American weekly newspaper in Kansas City, Missouri and Kansas City, Kansas.

Like his father, Wilkins opposed Jim Crow Laws. His activism led him to New York City where he became the assistant NAACP secretary under Walter Francis White. He later replaced W.E.B. Du Bois as editor of The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP.

Wilkins chaired the National Emergency Civil Rights Mobilization consisting of over one hundred local and national groups.

Along with A. Philip Randolph, founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and Arnold Aronson, a leader of the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council, Wilkins founded the Leadership Council on Civil Rights (LCCR), the premier civil rights coalition in the United States since 1957.

Wilkins became the executive secretary of the NAACP in 1955 and its executive director in 1964.

In response to actions by members of White Citizens Councils in Mississippi to deny credit to anyone involved in supporting civil rights initiatives, Wilkins provided support to civil rights activists as his first official action as executive director. Black businesses and activists opened accounts at the black-owned Tri-State Bank of Memphis, Tennessee which extended loans to credit worthy businesses denied by white-owned banks in Mississippi.

Wilkins participated in the Selma to Montgomery marches and the March Against Fear.

He supported nonviolent methods of opposing racial discrimination testifying at Congressional hearings and meeting with Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Carter. He earned the nickname, “Mr. Civil Rights,” and opposed militancy in the black power movement believing violence and calls for the separation of blacks and whites was a mistake. Wilkins initially warned against the direct actions of groups such as the Freedom Riders but came to respect and support their methods when passive attempts at integration failed.

Wilkins favored integration over desegregation, But the process proved to be slow and inefficient. Younger members criticized his moderate views and desire to avoid direct confrontations.

During his tenure, the NAACP played a pivotal role in key civil rights victories such as Brown V. Board of Education, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In 1968, he chaired the U.S. delegation to the International Conference on Human Rights. After his seventieth birthday in 1971, Wilkins began facing pressure to step down as executive director of the NAACP, but he refused to retire until 1977. He died in 1981.