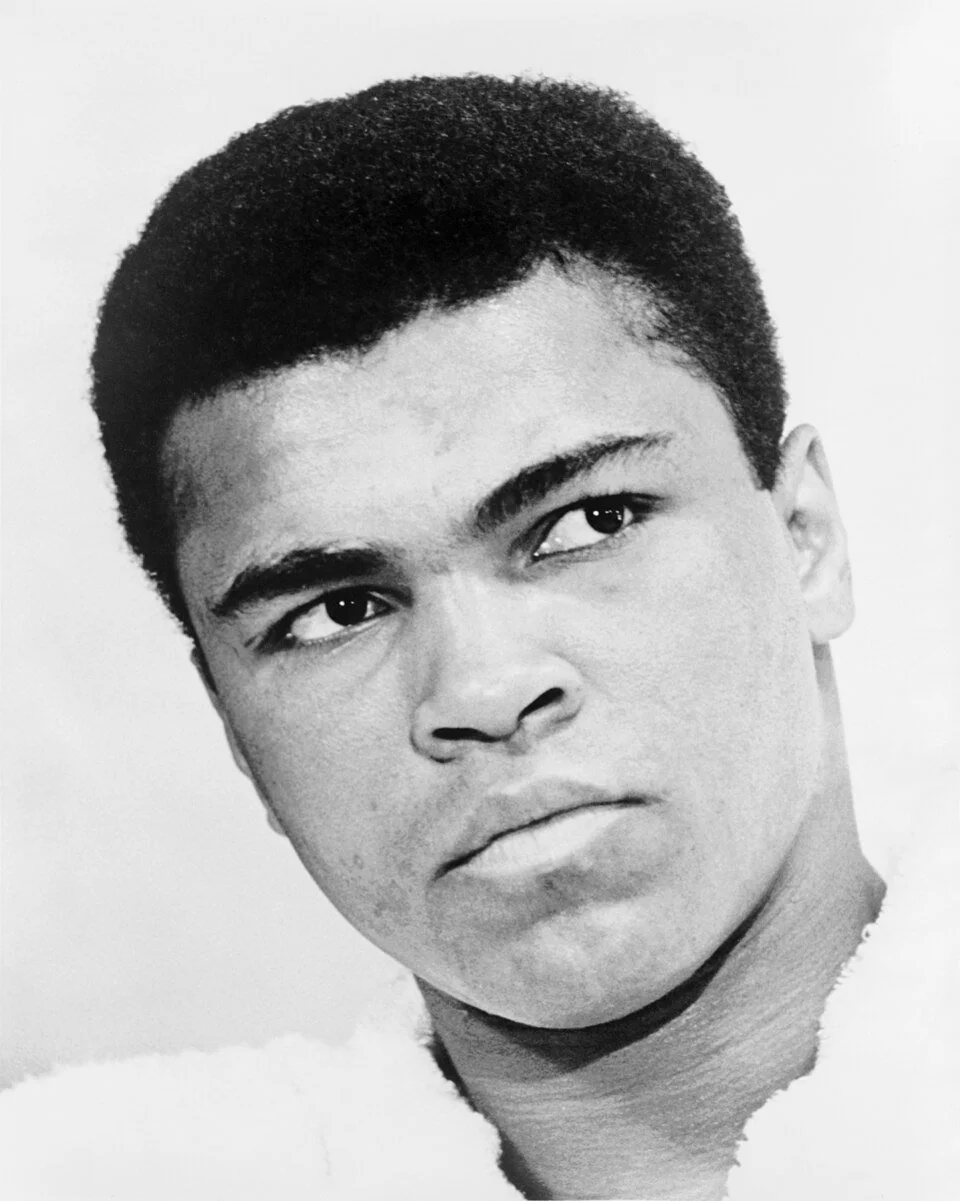

This month I have selected two individuals who made significant contributions to the Civil Rights movement. As the wife and widow of civil rights activist Medgar Evers, Myrlie Evers- William’s efforts were sometimes overlooked. After winning an Olympic Gold medal in boxing for the United States in 1960, Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. returned home to Louisville, Kentucky only to be refused service at a “whites-only” restaurant. Plagued by racial discrimination Clay became a follower of Malcolm X and converted to Islam changing his name to Muhammed Ali. Ali’s activism was often overshadowed by his celebrity status.

Born Myrlie Beasley on March 17,1933, in Vicksburg, Mississippi, She was raised by her paternal grandmother and an aunt after her parents separated. She excelled at school and was involved in many extracurricular activities.

Myrlie attended Alcorn A&M College, one of the few colleges in the state that accepted African American students. There, she met and fell in love with Medgar Evers, a World War II veteran who was eight years older than her. After they married, Myrlie let school and went to work at an insurance company. Medgar applied to law school while stealthily working to expand voting rights for Blacks in the Delta.

When Medgar became the Mississippi field secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1954. Myrlie worked alongside him as his secretary helping to organize voter registration drives and civil rights demonstrations. She was by his side as he fought to end the practice of racial segregation in schools, other public facilities, and the University of Mississippi.

Medgar became the target of pro-segregationist violence and terrorism. In 1962, their home was firebombed after Medgar and Myrlie organized a boycott of downtown Jackson Mississippi’s white merchants. The Evers had three young children. Their family was threatened and targeted by the Ku Klux Klan. Medgar was murdered in 1963 by Byron De La Beckwith, a member of the White Citizens’ Council in Jackson. De La Beckwith used a rifle to shoot Evers in the back as he was walking into his home. Myrlie and the children were home at the time ready to greet him. Medgar died several hours later at the hospital.

De La Beckwith was tried twice on a murder charge, but two all-white male juries each ended in hung juries. After failing twice to secure a conviction or an acquittal, the district attorney’s office declined to refile charges. De La Beckwith went free in 1965.

A year before De La Beckwith’s release in 1965, Myrlie moved her family to Claremont, California where she became an activist in her own right. She went back to school to earn her Bachelor of Arts in sociology from Pomona College. She began speaking for the NAACP.

In 1967, she co-wrote, For Us, the Living, a book about her late husband’s life and work.

Myrlie made two unsuccessful runs for U.S. Congress. Undeterred by her losses, she found other ways to serve her community including serving as the director of planning at the center for Educational Opportunity for Claremont Colleges and the national director for community affairs for the Atlantic Richfield company (ARCO). She helped secure funding for several organizations such as the National Woman’s Education Fund, and she worked with a group that provided meals to the poor and homeless. During this time, she met and married her second husband, Walter Willliams. They were together until his death in 1995.

Los Angeles mayor Tom Bradley appointed Myrlie to the Board of Public works as its first female commissioner. She also worked with the NAACP in the mid-nineties to help restore its tarnished reputation.

Myrlie never gave up the fight to see De La Beckwith brought to justice. Finally in 1994, based on new evidence, he was convicted of Medgar Evers’ murder and sentenced to life in prison where he died in 2001 at the age of 80.

Myrlie has received seven honorary doctorates. She was voted Ms. Magazine’s Woman of the Year, and Ebony Magazine named her one of the “100 Most Fascinating Black Women of the Twentieth Century.”

Muhammed Ali was born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. on January 17, 1942, in Louisville, Kentucky. He died June 3, 2016, in Scottsdale, Arizona after contracting a respiratory illness.

He began training as a boxer at age twelve. At eighteen he won a gold medal at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome, Italy and turned professional later that year.

In the ring, he was a champion, but in his home country the color of his skin often dictated where he was allowed to go and what he was allowed to do. Frustrated by racism and disillusioned by promises of rewards in heaven, he renounced Christianity and turned to Islam in the early 1960s.

After defeating Sonny Liston in 1964 to win the world heavyweight championship at twenty-two years old, Clay, who was named for a former slave owner turned abolitionist, decided to renounce his “slave name” and become Muhammed Ali.

Also in 1964, he began visiting Africa. In 1974, he visited a Palestinian refugee camp, and in 1978, he visited Bangladesh and became an honorary citizen.

Early in his career, he focused his charitable work on educating young people. He spoke at historically black colleges about the importance of education and in 1967, he became the largest single black donor to the United Negro College Fund after donating $10,000.

In 1967, while rich white men like Donald Trump were receiving multiple deferments to evade the Vietnam War draft, Ali was drafted. He refused to be drafted for religious reasons and ethical opposition to the Vietnam War. Ali was found guilty of draft evasion and stripped of his boxing titles. He stayed out of prison while appealing the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court. His conviction was overturned in 1971, but by then he had lost four years of peak athletic performance.

During those four years, Ali turned to activism speaking on college campuses in opposition to the Vietnam War, advocating for African American Pride, and racial justice. Ali was reviled by the American media on the grounds that his stance could lead to mass civil disobedience.

Ali’s comeback was powerful. He soon earned enough wins to be considered a top contender to regain the title from Joe Frazier. Their fight at Madison Square Garden was labeled “the Fight of the Century.” It occurred while his Supreme Court appeal was still pending. Ali and Frazier fought hard, but in the end Ali suffered his first professional defeat and lost by unanimous decision.

Ali continued his comeback and won his next bout against Frazier. His victory led to a fight for the title now held by George Foreman in Zaire. Billed as the “Rumble in the Jungle,” Foreman had youth, speed, and brute strength in his favor. Would Ali’s experience and determination be enough? Ali managed to frustrate Foreman to the point that he was swinging wildly and failing to land his punches. Ali dropped an exhausted Foreman with a combination, and Forman failed to get up before the count. Ali won his second heavyweight title by knockout. With an estimate one billion television viewers around the world, the fight was the world’s most-watched live television broadcast at the time.

In 1975, Ali and Frazier fought for a third time. The bout labeled “The Thrilla in Manilla,” took place in the Philippines. Ali won in the fifteenth round by a TKO after Frazier’s trainer refused to allow him to answer the bell because both of Frazier’s eyes were swollen shut. After the fight, Ali called Frazier the greatest fighter of all time and referred to their match as “the closest thing to dying that I know.”

In 1978, Ali, along with singer Stevie Wonder and actor Marlon Brando, participated in the Longest Walk, a protest march in the United States in support of Native American rights.

Ali’s actions as a conscientious objector helped bring to light disparities between the numbers of black and white men being drafted and sent into combat, and especially to the front lines. It also exposed a system where White men received most of the deferments granted. Black men who applied for deferments for the same reasons were more often denied.

Ali considered retiring but continued to fight until 1981.

He became an icon for the counterculture that opposed Vietnam, and a source of racial pride for African Americans during the Civil Rights movement and through his career.

Outside boxing, Ali performed as a spoken word artist releasing two studio albums. Both were nominated for Grammys. He also released two autobiographies.

He retired from boxing and concentrated on religion, activism, and philanthropy. He focused on practicing his Islamic duty of charity and good deeds donating millions of dollars to charitable organizations and disadvantaged people of all religious backgrounds. During his lifetime, it’s estimated that Ali helped to feed more than 22 million people afflicted by hunger around the world. In 1984, he announced that he had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s syndrome.

Ali was married four times, and fathered nine children.